On the afternoon of Feb. 1, 1960, in Greensboro, N.C., four North Carolina A&T students sat down at the Woolworth’s “whites only” lunch counter and ordered coffee. Denied service, they were asked to leave but remained seated until the store closed. Within weeks, their sit-in movement had spread to dozens of cities across 13 states.

On March 16, 1960, San Antonio became the first Southern city to negotiate a city-wide desegregation of lunch counters. One of those counters was in the downtown Woolworth on the corner of Alamo and East Houston streets, which remained a Woolworth until 1997, when the retailer left San Antonio. Many San Antonians probably know more about the 1997 closing of the retailer than realize it’s a special place in the civil rights movement.

Four days later, Jackie Robinson, Major League Baseball’s first African-American player, told The New York Times the story of San Antonio’s peaceful lunch counter integration “should be told around the world.”

Now the 1921 building is home to a Jimmy John’s, a dessert shop called Belgian Sweets, a Tomb Raider 3D ride, and Ripley’s Haunted Adventure, and with nothing to signify the events that transpired nearly 59 years ago. And its future—along with the adjoining 1923 Palace theater and the 1882 Crockett buildings—is uncertain.

In December, two months after the City Council approved the controversial Alamo Plaza plan on Oct. 18, one that’s intended to turn the plaza into a museum and larger public space, four preservation groups formed the Woolworth Coalition—San Antonio Conservation Society, San Antonio African American Community Archive and Museum (SAACAM), Westside Preservation Alliance, and Esperanza Peace and Justice Center. They want the former dime store and its historical significance preserved and not be shoved aside for the 1836 battle between Texian and Mexican forces.

The Alamo plan, which was approved by a series of committees composed of citizens and officials at local and state levels, places a museum where the three buildings stand on the plaza. However, renderings released to the public last year show variations of what the museum could look like—including, preserving the buildings, retaining the facades, or razing the buildings to make way for new construction.

The one certainty, officials said, was the location of the ground’s main entry point—through the Alamo museum and visitors center where the Crockett building currently stands across from the Alamo facade. Whether that meant the building would stay or be razed, no one could—and still can’t—answer.

In recent interviews, District 1 Councilman Roberto Treviño said an architect to design the museum and a firm to study the “integrity and the value historically of the (Woolworth) building” would be hired and announced this month.

“We don’t have a demolition list,” Treviño said. “We have no preconceived notions about what is going to be designed. That is up to the architect that we select.”

But vagueness of the plan, and the refusal by leaders, such as Treviño and others, to assure the buildings won’t be razed for a new Alamo museum, continue to spike concern.

“No one has said we’re definitely tearing it down, but as you see from those pages, it’s sort of … you’re setting it up for failure,” said Vincent L. Michael, executive director of the San Antonio Conservation Society and a member of the coalition.

During the public process last year, Alamo Plaza planners floated the idea of demolition. One of the reasons was because the floors of the Woolworth, Palace and Crockett buildings don’t align—an explanation the Conservation Society found unconvincing.

“It’s really a stupid argument,” San Antonio Conservation Society President Susan W. Beavin said. “I can’t think of a nicer adjective.”

Beavin continued, “Most good architects will tell you that a lot of your famous museums in Europe have uneven floors. It’s like they’ve just pulled everything they can out of the air that they think might be believable to be an argument.”

In response, the conservation society has hired its own architect to provide renderings of how the three buildings could be repurposed into a museum without having to demolish them.

“These will be ready soon,” Beavin said in an email this week, adding that her group will announce the architect at the same time.

During the public debate last year, some people—such as Forrest Byas, a member of the Alamo Citizens Advisory Committee who was interviewed by the San Antonio Express-News—argued for the razing of the buildings for the reconstruction of the west wall, which was “the scene of some of the heaviest fighting during the famous 1836 battle,” Express-News reporter Scott Huddleston wrote.

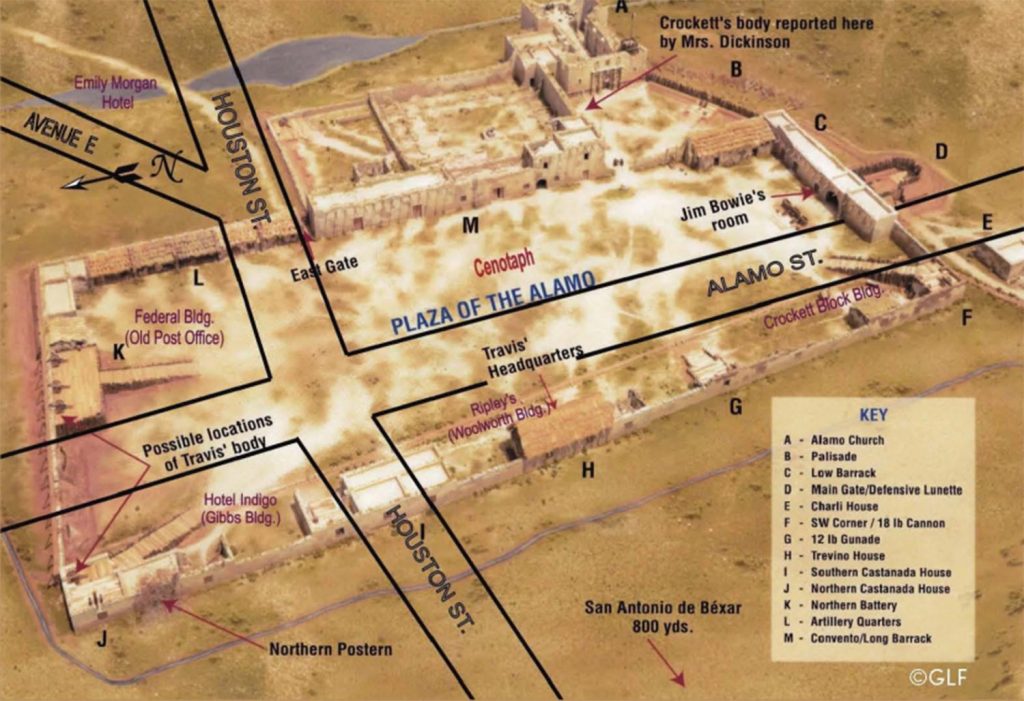

Using that logic, Michael and Beavin asked: Why not move the Hipolito F. Garcia Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse? The federal building stands on the location of the Alamo’s north wall, where Mexican Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna marched through, and where Lt. Col. William B. Travis died, they said.

Beavin later added, “Everybody is stuck on the Alamo, ‘Oh, let’s take down the buildings so we can show the west wall.’ Well they’re not suggesting taking down the federal post office, which was the north wall. So it’s like pick and choose: you want it all or not? And it doesn’t address any of what went on at the Woolworth, the significance of any of the African-American heritage and culture that was very prevalent.”

So far, this year

The Alamo Management Committee, which includes Treviño, and two members each from the Alamo Endowment (the plan’s primary funder) and the Texas General Land Office (GLO), continues to meet, Assistant City Manager Lori Houston said in an email.

“The concerns about the Woolworth building have been discussed and will continue to be discussed until a recommendation is made,” Houston said, referring to the team that will design the museum and assess the buildings.

Representatives at the GLO did not respond to interview requests, and Douglass McDonald, CEO of the Alamo Trust Inc., declined to be interviewed.

During an East Side meeting Feb. 7 at the Claude Black Community Center, District 2 Councilman Art Hall said, “My understanding is that the (Alamo) plan is amended so that the Woolworth building is not going to be part of the demolition. I’m getting more info as we move forward, but that’s my understanding.”

Hall changed his position slightly the following Wednesday. Following a City Council B session meeting, in a joint interview with Hall and Treviño, Hall deferred questions about the Woolworth building to Treviño.

When asked why a historical assessment of the Woolworth was needed, considering the fact that no one disputes the civil rights events that transpired there in March 1960, Treviño said, “What this person is going to document is the actual history of the building both tangible and intangible.”

Why this Woolworth?

Despite uncertainty as the Alamo plan moves forward, La Juana Chambers Lawson, a leader at SAAACM, is optimistic that if things are handled correctly, and the former home of the Woolworth is preserved, there will be new opportunities to tell the largely unknown stories extending past 1836 in the plaza.

“What we would like (is) for us to have the opportunity to tell the story of African-Americans here in San Antonio,” Lawson said. “Preserving the Woolworth building would give us the opportunity to really bring out those stories that we just forgot about.”

Beavin added, “The whole story of the African-American presence, not just at Woolworth, but there in the plaza, is something that most people—even most of the African-American population—are unaware (of). It’s significant, so it’s another reason the building needs to tell the Woolworth story as well as being part of the museum.”

The question remains why this Woolworth has received so much attention given that it was one of seven locations that desegregated its lunch counters, according to the conservation society’s research.

Beavin mentioned the other notable location is the Kress building, two blocks west on Houston Street, which is home to a Texas de Brazil steakhouse; and the building’s owner, GrayStreet Partners, is planning to convert the upper floors into office space. Others around the plaza include the old H.L. Green building, which is the current home of Ripley’s Believe It or Not!.

The Houston and Alamo corner is the focus of preservation because of its prominent downtown location, according to members of the coalition.

Also, most of the sit-ins across the South occurred in places with larger African-American populations and more pronounced racial turmoil. That San Antonio would be the city leading the nation in desegregating lunch counters and doing it quickly, and with no conflict, makes the downtown Woolworth even more noteworthy. Coalition members credit city and religious leaders of that era and cite the heavily-trafficked bus stop near the downtown Woolworth as a melting pot where many cultures met from farther reaches of the city.

“Being at the prominent corner of Houston and Alamo, the Woolworth corner was where many people changed buses,” Michael said. “Especially if they were heading to the East and West sides they would catch the bus on Houston at Alamo.”

Despite the significance of the events, the desegregation was quiet. In the days following March 16, 1960, local newspapers gave the story very little coverage, according to Heron research.

“You know why the story doesn’t get told? Because there wasn’t any conflict. You know conflict—if it bleeds it leads. Conflict sells papers,” Michael said. “To try to tell the story of a city that did it peacefully where everyone gets along is not a good story.”

Editor Ben Olivo contributed to this report.

Setting It Straight: The original version of this article misstated the year the Woolworth building was built, which was 1921.

Resources

» “From Crockett to the Civil Rights Movement: Layers of Significance on Alamo Plaza,” prepared by the city’s Office of Historic Preservation (2018)

» San Antonio Express-News: Historic events collide at the site of Woolworth building (Sept. 24, 2018)

Ben,

Just a quick note that the Woolworth Bldg iwas built in 1921, not 1912. Thanks for reposting.

Susan

Just saw this. Correcting now.

This building must remain due to its great architecture and history.

So the same councilmember who derided Beacon Hill Elementary students, families and staff for wanting a long-neglected and derelict building demolished – and who held a cash-strapped inner-city school district hostage via his pet-project, forced curriculum – is siding with outside planners and architects and complicity supporting the demolition of the Woolworth building? A building in far better shape and with greater historical reference than the Beacon Hill Elementary.