By Bryan Rindfuss | San Antonio Current

Just before the turn of the last century, artist Anne Wallace won a commission to embark on a years-long public art project exploring the rich history of Lavaca — San Antonio’s oldest continuously inhabited neighborhood.

However, that commission came with an unusual stipulation: her artwork needed to be integrated into the sidewalks.

Taking cues from Ed Gaida’s 1999 book “Sidewalks of San Antonio” — a pictorial history that documents insignias left behind by concrete crews — Wallace set out to cement an enduring portrait of the neighborhood.

In search of stories that would illustrate Lavaca’s fascinating past lives, she conducted research at the Institute of Texan Cultures and the San Antonio Public Library’s Texana collection, combed through old city directories and Sanborn maps, attended neighborhood association meetings and spread the word organically. Her primary goal was to locate and interview residents with clear memories of how things once were — especially before urban renewal projects like the Victoria Courts and Hemisfair forced out ethnically diverse families and forever altered the flow between Lavaca and downtown San Antonio.

“I really wanted to find stories of people that remembered that far back,” Wallace said. “Little by little … I started finding people who’d been in the neighborhood a long time. … It was really amazing. The emotion of older people of the neighborhood getting cut off from downtown by Victoria Courts and by Hemisfair was pretty powerful. I got this real sense of this constant motion back and forth, where everyone in this part of town socialized downtown, shopped downtown, walked to events downtown, and that all just kind of got cut off by these urban renewal projects. Of course, the courts and Hemisfair razed big chunks of the neighborhood and forced all those people out.”

From the oral histories she collected, Wallace created “The Unofficial Story” — a poignant collection of anecdotes she stamped into sidewalks that border the neighborhood’s quaint pocket parks.

Although visually unassuming, these curious slices of life can conjure vivid scenes: a family going to view Geronimo as he was being held as a prisoner of war at Fort Sam Houston; a San Antonio native whose grandfathers fought on opposing sides of the Mexican Revolution; oompah music filling the air; segregated dances being held at the Municipal Auditorium; a “block party” atmosphere shared by German, Hispanic, Czech and Jewish neighbors. Mentions of food also abound: beans, tamales, tortillas, oxtail, rabbit, squirrel, beef brains and scrambled eggs.

As complements to the anecdotes, Wallace created symbolic stamps to reference languages spoken in the neighborhood — Coahuiltecan, English, Spanish, German, Polish, Chinese — and the area’s use as croplands for the Alamo.

She also etched historic photographs into the concrete, including an exterior image of the Garden Fruit Store in the 1920s, a Mexican American family gathered around the dinner table in the 1930s and a man serving coffee at the Pig Stand in the 1950s.

Now two decades after The Unofficial Story began taking shape, Wallace recently got her portable typesetting system back out to recreate a portion of the project that was destroyed when sidewalks were torn out as part of a condo development on Florida Street.

In addition to photographing the restoration process, we took the opportunity to speak to Wallace about the project’s enduring highlights and its unique ability to convey place and time.

Wallace uses her body weight and a sledgehammer to ensure the stamp makes an even impression in the wet concrete.

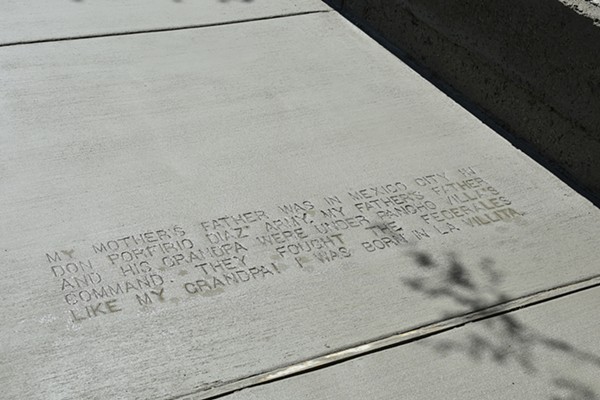

Freshly restored, a beloved anecdote reads “My mother’s father was in Mexico City in Don Porfirio Diaz’ Army. My father’s father and his grandpa were under Pancho Villa’s command. They fought the federales like my grandpa! I was born in La Villita.

During the planning stages of the project, Wallace happened upon a man who shared this powerful anecdote: “I remember when they pulled the last old lady out. She was in a wheelchair. When they tore everything down for HemisFair, that’s when I became familiar with eminent domain.”

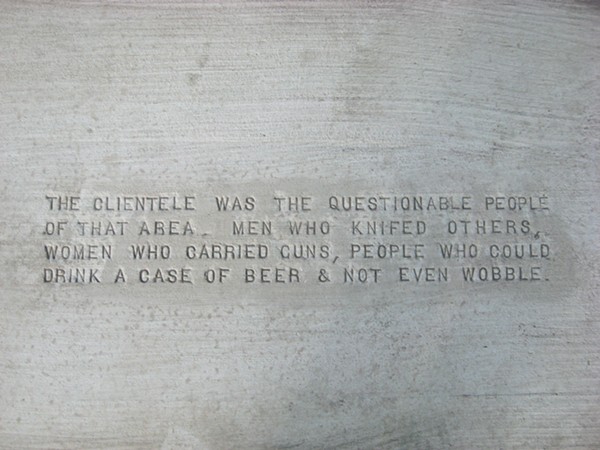

This anecdote about a watering hole in the vicinity of Bar America is rightfully among the fan favorites of The Unofficial Story. “The clientele was the questionable people of that area. Men who knifed others, women who carried guns, people who could drink a case of beer and not even wobble.” With a laugh, Wallace confessed, “I was afraid the city would tell me I couldn’t use it!”

This photoengraving depicts the Beltrán Espinoza family in the 1930s. Through interviews with family members, Wallace learned about the Xochimilco Social Club, a group that gathered in the Beltrán Espinoza’s backyard for gorditas and good times.

Attorney Kat McColley Doucette purchased the Beltrán Espinoza family’s 1910 home and found the Xochimilco Social Club’s original sign in a dilapidated garage. After learning that the club was mentioned in “The Unofficial Story,” she photographed the sign and recently sent the picture to Wallace. “It makes me very happy that the sidewalk project is connecting people across time, space and generations,” Wallace said.

From left: Ricardo Torres, Jairo Torres, Juan Carlos Reyes Bautista and Erik Jonas Reyes represent three generations who all work for the family business Bautista Concrete Work. Although they were hired to pour the sidewalks, they were unaware of Wallace’s restoration project. “[They] had no idea they were expected to work with me on this,” Wallace said. “It was hot as hell out there … [but] they were wonderful.”

This article is republished with permission from the San Antonio Current.

The San Antonio Current, San Antonio’s award-winning alternative media company, has served as the city’s premiere multimedia source of alternative news, events and culture since 1986.